Introduction

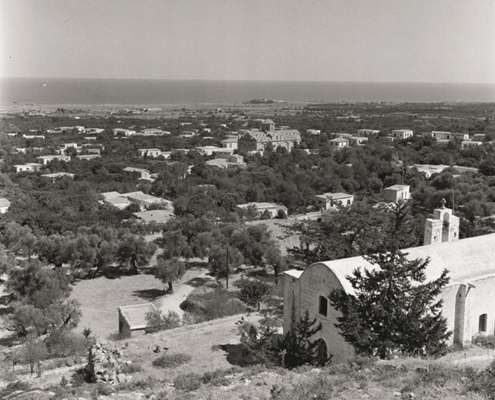

The town of Karavas lies on the north coast of Cyprus, in the occupied district of Kyrenia. All the residents of Karavas, around 4,000, were forced to abandon their homes and properties in 1974, as a result of the Turkish invasion.

The displaced municipality of Karavas now operates in the government-controlled areas, in Nicosia. The municipality’s main goals are to strengthen the relations between its scattered residents, to promote the area’s history and culture, as well as to reinforce and support the efforts for a just and viable solution to the Cyprus problem; a solution that will enable the return of all refugees to their ancestral homes under conditions of freedom and dignity and which will secure and safeguard their human rights.

The area of Karavas has always been inhabited since the Prehistoric times. Remains of the Neolithic Era were found in the area called “Gyrisma”, in the town’s “Pano Gitonia”. Clay vessels of the Geometric and Archaic period were also discovered in other areas of Karavas.

Within the municipal boundaries of Karavas, very close to the sea, in the area called “Katalymata”, lies the acropolis of the ancient city of “Lambousa”. It prospered from the Classical period to the Early Byzantine period, but it was ultimately destroyed by the Arabs in the 7th C. The famous “Lambousa Treasures” found in the area, which include objects like jewellery, religious items and silver spoons demonstrate its economic and cultural growth. The most important artefacts of the treasure is a collection of nine silver trays depicting scenes from the life of David. Items of the Lambousa treasures are kept in the Archaeological Museum of Cyprus, the New York Metropolitan Museum, the British Museum, and in other museums abroad.

During the Medieval Period (14th – 15th C.), the settlement “Prastio di Caravo” existed, to which the church of Acheiropoietos belonged.

Lambousa Treasures

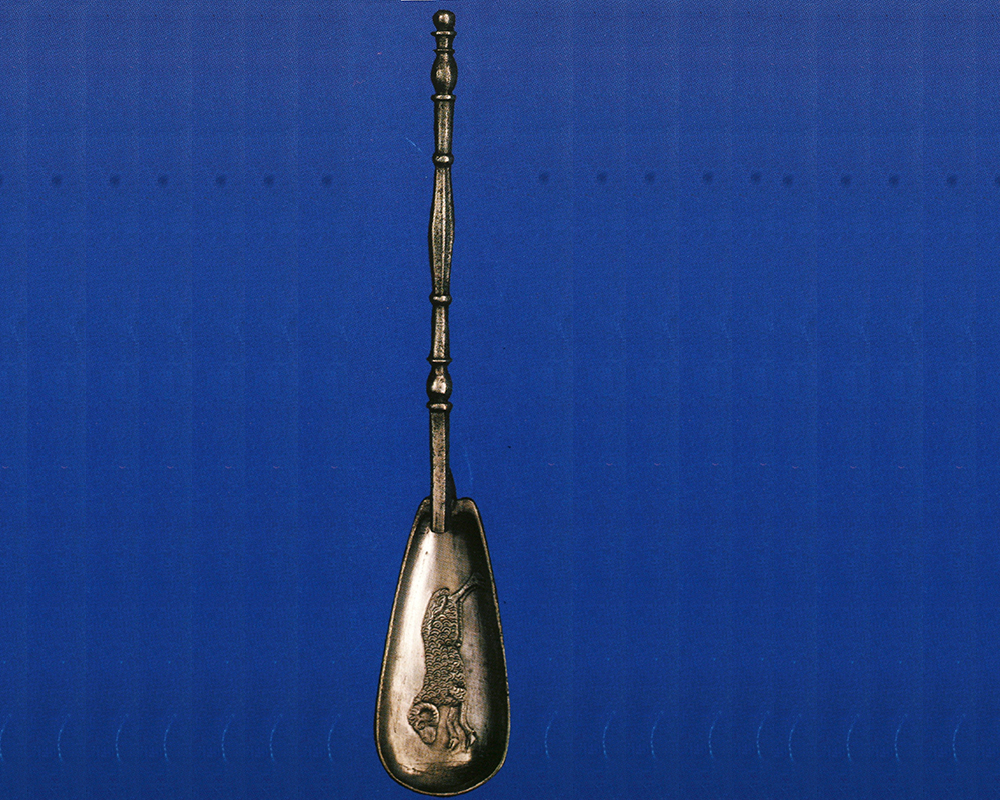

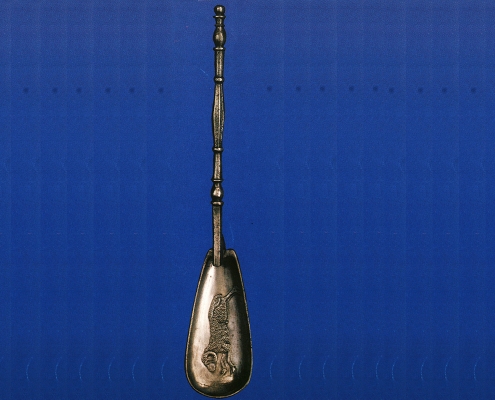

The first treasure was found during the late 19th century and the British Museum bought a large portion of it in 1899. This treasure includes a silver thurible decorated with the forms of Christ, the Virgin Mary and Apostles Peter, Paul, John and Jacob, a large deep tray, a smaller tray and a number of silver spoons, 24 of which bear various representations andare in the British Museum.

According to sources, the first Lambousa treasure includes another 12 silver spoons and there is no information regarding their

whereabouts.

The smallest of the two trays of the First Treasure of Lambousa’s is 24.5 cm in diametre and resembles a bowl, since its depth reaches 7.8 cm. The circumference of the tray is decorated with a wide anastatic band composed of two circles with jewellery or fleuron resembling shields. In the centre there is a wide engraved belt of vegetal blastus enclosing the form of a martyr saint, usually recognised as Saint Sergios.

The other tray measures 26.9 cm in diametre. In the centre there is a circular engraved belt of vegetal blastus enclosing a cross with a technical niello.

In niello technique the picture is engraved on gold or silver. Firstly, the picture is engraved with a sharp instrument. Then a black mixture of lead, silver, copper, sulphur and borax is poured on the gold or silver plate, and that it why it is called niello, from the Latin nigellum. Then the plate is placed on fire, the niello melts and spreads over the engravings. When the plate is cold, the excess material is removed with various scrapers.

The plate with the form of Saint Sergios was made, as one can deduct from the seals, during the reign Constantine III between 641-651 AD, while the other tray was made during the reign of Emperor Tiberius between 578-582 AD.

The second treasure was discovered in 1902, or according to the local version, in February 1902 in the acropolis of Lambousa known as “Troullia”, and is larger and more significant than the first treasure.

Unfortunately, only a part of this treasure was confiscated by the Police and handed over to the Museum of Cyprus. The largest part was smuggled out of the country and most artefacts were bought in 1906 in Paris by John Pierpont Morgan, who then loaned the artifacts to the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, where an exhibition was organised for the public. In 1917, Pierpont Morgan’s son granted the treasure to the New York Metropolitan Museum. The treasure consists of nine silver trays with anastatic pictures from the life of David, five silver trays with various monogrammes in the centre, as well as gold objects, such as medals, necklaces, bracelets, earrings, and crosses. Some of the pieces of the treasure were sold separately, such as the gold encolpion that is now to be found in the collection of Dumbarton Oaks in Washington.

All the trays with pictures from the life of David bear seals in the form of Emperor Heraclius, his monogramme, the monogramme of “comes sacrarum largitionum Theodoros”, and the names Theochristos, Komitas, Scholastikis and Kosmas, which belong to those who sealed the silver. Thus, the trays with scenes from the life of David can be dated between 613 and 630 AD.

Trays in the Museum of Cyprus

In the Museum of Cyprus, which is found on 1, Mouson Avenue, a few metres away from the demarcation line, there is a total of five trays from the second treasure of Lambousa. The three are decorated with scenes from the life of David inspired from the Old Testament and the other two trays bear monogrammes in the centre. Following is a short description of these trays.

- Tray 14 cm in diametre (photo 1). This tray portrays David seated on a rock with his lyre in his left hand, receiving Samuel’s messenger. On the lower part one can see two sheep and vegetal blastus in the scenery, while on the upper part the sky and sun, the moon and stars. This compilation is reminiscent of the mythological scene of musical Orpheus.

Tray 14 cm in diametre (photo 2). This tray depicts David kneeling with his left leg on the back of a bear, which he holds by the head with his left hand and prepares to kill it with the club he is holding in his right hand. On the left the space is filled by a tree. The scene is reminiscent of the first labour of Hercules with the lion of Nemea.

- Tray 26.8 cm in diametre (photo 3). This tray depicts the wedding of David with Samuel’s daughter, Melchior. The scene is depicted in front of a gate. Saul is in the centre and David is seen in front holding Melchior’s hand. On the edges are two young men playing the flute. On the lower part there is a basket with fruit and two “purses” symbolising blessings.

- Tray 44 cm in diametre (photo 4). In the centre of this tray there is an engraved circular decorative band with vegetal blastus surrounding a cross-shaped monogramme, which can be read either Ioannou or Antoniou with technical niello. The imperial seal is of Emperor Phokas and thus the tray was made between 602-610 AD.

- Tray 36 cm in diametre (photo 5). This tray is decorated with gilded gold circles with engraved vegetal blastus surrounding a circular cross made with technical niello. This tray was made during Emperor Heraclius’ reign between 613-630 AD, as the seals demonstrate.

Trays kept in museums abroad

From the second treasure of Lambousa, six trays with scenes from the life of David, as well as three others with cross-like monogrammes are in various museums of the United States.

The six trays with scenes from the life of David are in the New York Metropolitan Museum. The three silver trays with monogrammes are in the following museums:

The first tray, measuring 13.4 cm in diametre, is in the New York Metropolitan Museum and bears an engraved decoration with ivy blastus in a circle containing a monogramme in technical niello. The second tray of the same size and decoration is in the Dumbarton Oaks collection in Washington. The third tray, measuring 25.5 cm in diametre, similar to the previous two, is in the Walters Art Gallery of Baltimore.

Jewellery from the second treasure of Lambousa kept in the Museum of Cyprus

In the Museum of Cyprus, in Nicosia, there are various other gold objects, mainly jewellery from the second treasure of Lambousa.

In designing jewellery, the workshops in Constantinople were considered to produce the highest quality, without this meaning that other workshops across the empire were any less good . Byzantine jewellery included belts, bracelets, rings, earrings, necklaces and crosses, as well as various medals and talismans. Pearls and precious stones, niello and enamel combine their brilliance with the brightness of gold and silver. Some of the gold pieces of jewellery kept in the Museum of Cyprus are the following:

The necklace in photograph 6 is 26 cm long. It consists of seven amethysts among small pearls. They are joined with fine gold wires. On the ends are two small circles of gold clasps decorated with birds using the technique with holes. The cross, measuring 7.5×6 cm, that also comes from the second treasure of Lambousa, is made of a thick sheet of gold, decorated with an anastatic dotted surrounding.

The same technique was used on the tips of the cross that read “Rest the souls of Christina, Solononi and Sissini”.

The gold medals or coins hanging on necklaces or belts were of special importance to the Byzantines. The gold clasp in photograph 7 bears a coin from Justin II and Tiberius II with a leaf-like corner (29 cm long) made of loops joined by small eight-shaped rings. The clasp and chain are parts of two different pieces of jewellery. The Byzantine earrings are just as good as the other kinds of jewellery. The Museum of Cyprus also keeps a few samples of this kind of jewellery. One such example is found in photograph 8. These earrings consist of a collar with four hooks and on their lowest point four small chains hang ending in pearls (7.5 cm long). Of the most dominant types are the earrings in the shape of crescents, which are similar regarding the outer shape but have varying internal decoration with many geometrical shapes or animal motifs. A characteristic example of this are the two different earrings of the early Byzantine period (6th-7th century AD), as shown in photograph 9. One has a cross made in the technique with holes design in a circle between two facing peacocks (3.2 cm long). The other in the same technique shows two birds facing opposite directions and, in the middle, a vegetal motif (5 cm long).

These gold pieces of jewellery and some others kept in the Museum of Cyprus cannot be dated precisely. They also follow the technique and fashion of the period based on older models of the Hellenistic period.

There are differing views about the origin of the Lambousa jewellery. Some believe that they came from workshops abroad, such as Syria or Egypt. Given the fact that the technique used to create the jewellery was widespread in the Mediterranean region during the pro-Byzantine period, many believe that the jewellery was indeed designed in workshops in Lambousa, where goldsmithing and silversmithing flourished during that period.

Epilogue

What we can understand by examining the two Lambousa treasures is that Cyprus flourished during the pro-Byzantine period and especially during the 6th and 7th centuries. Lambousa was a prosperous town of that period and was at the same time the capital of one of the fifteen districts of Cyprus.

Lambousa may have had the grandeur and brilliance it had during the period from the 2nd to the 7th century AD only once, but the inhabitants managed to return after centuries of displacement, when in 965 AD Nikiforos Phokas liberated Cyprus from the Arabs. The only monuments that can be found today in the Lambousa area are the temples of Acheiropoiitos and Saint Evlalios, which indicate that the inhabitants maintained the fame and brilliance of Lambousa after the 10th century AD.

The town and treasures of Lambousa are a historical example that has several common attributes with the destruction Cyprus suffered in July 1974. The beautiful towns of Karavas and Lapithos, along with the rest of the occupied areas, took a heartless blow by the Turkish invaders. Many inhabitants in those days followed the example of the Lambousa inhabitants and hid gold objects and money in their gardens and houses in many cases, in the hope that as soon as the war was over they would return to find them. However, many years have passed and the hope keeps on piling year by year. For us, the wealth and history of Lambousa remain a historical example and at the same time a strong message for everyone. A message that originates from the fact that the conquerors come, pillage a land that does not belong to them and is not willing to allow them to send out roots. With these thoughts we soften the pain of bitter displacement and look towards the future with hope, always having in mind that no one can erase our ardent will to return.

With conviction and unwavering faith, we state that we shall return to Lambousa as victors and shall continue the tradition that our ancestors established and maintained.